Shinkendo

In feudal times the core aspect of any Japanese warrior's martial education was that of swordsmanship. Shinkendo is a comprehensive reunification of what the Samurai once used and relied upon for survival, and can be classified as a combination of the founder's own technical and structural innovations and an amalgamation of several traditions of Japanese swordsmanship that have been forced to evolve and splinter over time. Unified, Shinkendo is a historically accurate and comprehensive style of Japanese Swordsmanship.

In feudal times the core aspect of any Japanese warrior's martial education was that of swordsmanship. Shinkendo is a comprehensive reunification of what the Samurai once used and relied upon for survival, and can be classified as a combination of the founder's own technical and structural innovations and an amalgamation of several traditions of Japanese swordsmanship that have been forced to evolve and splinter over time. Unified, Shinkendo is a historically accurate and comprehensive style of Japanese Swordsmanship.

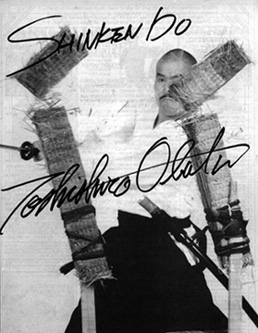

The Shinkendo school emphasizes very traditional and effective swordsmanship, which with serious training, leads to both practical ability as well as an understanding of classical martial arts. Shinkendo is steeped in the traditions of the samurai, in such ways as Heiho (strategy), Reiho (proper Bushido etiquette) and philosophy. Toshishiro Obata Kaiso is the founder, director and chief instructor of The Kokusai Shinkendo Renmei (International Shinkendo Federation), an organization dedicated to teaching authentic Japanese swordsmanship.

The Shinkendo school emphasizes very traditional and effective swordsmanship, which with serious training, leads to both practical ability as well as an understanding of classical martial arts. Shinkendo is steeped in the traditions of the samurai, in such ways as Heiho (strategy), Reiho (proper Bushido etiquette) and philosophy. Toshishiro Obata Kaiso is the founder, director and chief instructor of The Kokusai Shinkendo Renmei (International Shinkendo Federation), an organization dedicated to teaching authentic Japanese swordsmanship.

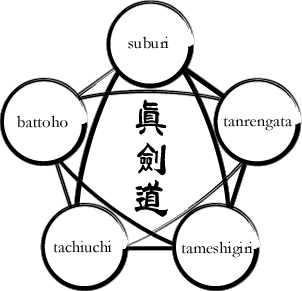

Goho Gorin Gogyo

Training in Shinkendo is balanced between five different streams of practice. These streams, called the Goho Gorin Gogyo, include:

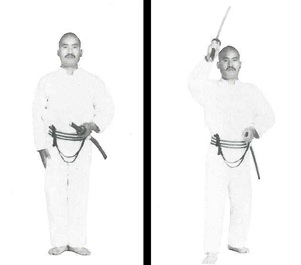

- Suburi (sword swinging drills),

- Tanrengata (solo forms),

- Battoho (combative drawing and cutting methods),

- Tachiuchi (sparring) and,

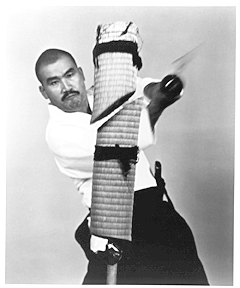

- Tameshigiri (cutting straw and bamboo targets).

Students always train using a Bokuto (wooden sword), and later advance to training with Iaito (non-sharpened sword) and finally Shinken, or 'live blade'. At more advanced levels, the student begins to test their acquired skills through test cutting practice on tatami omote makiwara (rolled up tatami mats, previously soaked in water), and eventually Take (Japanese or Chinese bamboo).

The goal of Shinkendo is to develop and harmonize the mind and body. Proficiency in swordsmanship and spiritual development are not sequential achievements; they are interactive and interdependent developments.

The serious practitioner should devote themselves to tireless practice of the techniques of the Goho Gorin Gogyo and embodiment of the principles and philosophy of Jinsei Shinkendo (life is Shinkendo).

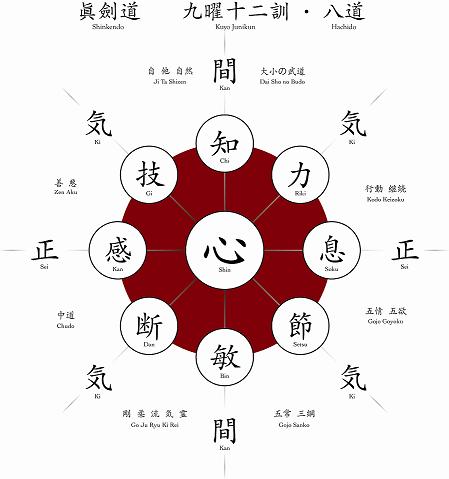

This is not to imply that one should become a senseless devotee of the art but rather that the concepts learned through Shinkendo should be used to improve and balance all areas of a practitioner's life. More succinctly one should seek to integrate the teachings and philosophy of the Kuyo Junikun (12 precepts of the nine planets stratagem) and the 8 ways of the Hachido into their daily lives.

The goal of Shinkendo is to develop and harmonize the mind and body. Proficiency in swordsmanship and spiritual development are not sequential achievements; they are interactive and interdependent developments.

The serious practitioner should devote themselves to tireless practice of the techniques of the Goho Gorin Gogyo and embodiment of the principles and philosophy of Jinsei Shinkendo (life is Shinkendo).

This is not to imply that one should become a senseless devotee of the art but rather that the concepts learned through Shinkendo should be used to improve and balance all areas of a practitioner's life. More succinctly one should seek to integrate the teachings and philosophy of the Kuyo Junikun (12 precepts of the nine planets stratagem) and the 8 ways of the Hachido into their daily lives.

Kuyo Junikun

While Shinkendo requires rigorous physical training, depth of coordination, and intense focus, one of the most important aspects of Shinkendo is the emphasis on spiritual forging, which inspires Bushi Damashii (the Samurai/ warrior spirit), a quality that is as relevant now as it was hundreds of years ago. Proper practice of Shinkendo should provide one with not only a strong body and mind, but also a calm, clear and focused spirit. It is this aspect of the training which can be carried into any part of one's life and thus makes Shinkendo as relevant now as it was a thousand years ago.

While Shinkendo requires rigorous physical training, depth of coordination, and intense focus, one of the most important aspects of Shinkendo is the emphasis on spiritual forging, which inspires Bushi Damashii (the Samurai/ warrior spirit), a quality that is as relevant now as it was hundreds of years ago. Proper practice of Shinkendo should provide one with not only a strong body and mind, but also a calm, clear and focused spirit. It is this aspect of the training which can be carried into any part of one's life and thus makes Shinkendo as relevant now as it was a thousand years ago.